|

FOREIGN AFFAIRS

January/February 2014

COMMENT

The Ever-Emerging Markets

Why

Economic Forecasts Fail

Ruchir Sharma

RUCHIR SHARMA is head of Emerging Markets and Global Macro at Morgan Stanley Investment Management and the author of Breakout Nations: In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles. In the middle of the last decade, the average growth rate in emerging markets hit over seven percent a year for the first time ever, and forecasters raced to hype the implications. China would soon surpass the United States as an economic power, they said, and India, with its vast population, or Vietnam, with its own spin on authoritarian capitalism, would be the next China. Searching for the political fallout, pundits predicted that Beijing would soon lead the new and rising bloc of the BRICs -- Brazil, Russia, India, and China -- to ultimate supremacy over the fading powers of the West. Suddenly, the race to coin the next hot acronym was on, and CIVETS (Colombia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Egypt, Turkey, and South Africa) emerged from the MIST (Mexico, Indonesia, South Korea, and Turkey). Today, more than five years after the financial crisis of 2008, much of that euphoria and all those acronyms have come to seem woefully out of date. The average growth rate in the emerging world fell back to four percent in 2013. Meanwhile, the BRICs are crumbling, each for its own reasons, and while their summits go on, they serve only to underscore how hard it is to forge a meaningful bloc out of authoritarian and democratic regimes with clashing economic interests. As the hype fades, forecasters are left reconsidering the mistakes they made at the peak of the boom. Their errors were legion. Prognosticators stopped looking at emerging markets as individual stories and started lumping them into faceless packs with catchy but mindless acronyms. They listened too closely to political leaders in the emerging world who took credit for the boom and ignored the other global forces, such as easy money coming out of the United States and Europe, that had helped power growth. Forecasters also placed far too much predictive weight on a single factor -- strong demographics, say, or globalization -- when every shred of research shows that a complex array of forces drive economic growth. Above all, they made the cardinal error of extrapolation. Forecasters assumed that recent trends would continue indefinitely and that hot economies would stay hot, ignoring the inherently cyclical nature of both political and economic development. Euphoria overcame sound judgment -- a process that has doomed economic forecasting for as long as experts have been doing it. SINGLE-FACTOR SYNDROME History shows that straight-line extrapolations are almost always wrong. Yet pundits cannot seem to resist them, lured on by wishful thinking and fear. In the 1960s, the Philippines won the right to host the headquarters of the Asian Development Bank based on the view that its fast growth at the time would make the country a regional star for years to come. That was not to be: by the next decade, growth had stalled thanks to the misguided policies of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos (but the Asian Development Bank stayed put). Yet the taste for extrapolation persisted, and in the 1970s, such thinking led U.S. scholars and intelligence agencies to predict that the future belonged to the Soviet Union, and in the 1980s, that it belonged to Japan. Then came the emerging-market boom of the last decade, and extrapolation hit new heights of irrationality. Forecasters cited the seventeenth-century economic might of China and India as evidence that they would dominate the coming decade, even the coming century. The boom also highlighted another classic forecasting error: the reliance on single-factor theories. Because China’s boom rested in part on the cheap labor provided by a growing young population, forecasters started looking for the next hot economy in a nation with similar demographics -- never mind the challenge of developing a strong manufacturing sector to get everyone a job. There were the liberals, for whom the key was more transparent institutions that encouraged entrepreneurship -- despite the fact that in the postwar era, periods of strong growth have been no more likely under democratic governments than under authoritarian ones. And then there were the moralizers, for whom debt is always bad (a bias reinforced by the 2008 credit crisis), even though economic growth and credit go hand in hand. The problem with these single-factor theories is that they lack any connection to current events or an appreciation for the other factors that make each country unique. On the one hand, institutions and demographics change too slowly to offer any clear indication of where an economy is headed. On the other, those forecasters who have argued that certain national cultures are good or bad for growth miss how quickly culture can change. Consider Indonesia and Turkey, large Muslim-majority democracies where strong growth has debunked the view of Islam as somehow incompatible with development. Sweeping theories often miss what is coming next. Those who saw geography as the key factor failed to foresee the strong run of growth during the last decade in some of the most geographically challenged nations on earth, including landlocked countries such as Armenia, Tajikistan, and Uganda. In remote Kazakhstan, rising oil prices lifted the economy out of its long post-Soviet doldrums. The clarity of single-factor theories makes them appealing. But because they ignore the rapid shifts of global competition, they provide no persuasive scenario on which to base planning for the next five to ten years. The truth is that economic cycles are short, typically running just three to five years from peak to trough. The competitive landscape can shift completely in that time, whether through technological innovation or political transformation. HERE AND NOW Indeed, although forecasters hate to admit it, the coming decade usually looks nothing like the last one, since the next economic stars are often the last decade’s castoffs. Today, for example, formerly stagnant Mexico has become one of the most promising economies in Latin America. And the Philippines, once a laughingstock, is now among the hottest economies in the world, with growth exceeding seven percent. Dismissed on the cover of The Economist five years ago as “the world’s most dangerous place,” Pakistan is suddenly showing signs of financial stability. It had one of the world’s top-performing stock markets last year, although it is being surpassed by an even more surprising upstart: Greece. A number of market indices recently demoted Greece’s status from “developed market” to “emerging market,” but the country has enacted brutal cuts in its government budget, as well as in prices and wages, which has made its exports competitive again. What these countries’ experiences underscore is that political cycles are as important to a nation’s prospects as economic ones. Crises and downturns often lead to a period of reform, which can flower into a revival or a boom. But such success can then lead to arrogance and complacency -- and the next downturn. The boom of the last decade seemed to revise that script, as nearly all the emerging nations rose in unison and downturns all but disappeared. But the big bang of 2008 jolted the cycle back into place. Erstwhile stars such as Brazil, Indonesia, and Russia are now fading thanks to bad or complacent management. The problem, as Indonesia’s finance minister, Muhammad Chatib Basri, has explained, is that “bad times make for good policies, and good times make for bad policies." The trick to escaping this trap is for governments to maintain good policies even when times are good -- the only way an emerging market has a chance of actually catching up to the developed world. But doing so proves remarkably difficult. In the postwar era, just about a dozen countries -- a few each in southern Europe (such as Portugal and Spain) and East Asia (such as Singapore and South Korea) -- have achieved this feat, which is why a mere 35 countries are considered to be “developed.” Meanwhile, the odds are against many other states’ making it into the top tier, given the difficulty of keeping up productivity-enhancing reforms. It is simply human nature to get fat during prosperity and assume the good times will just roll on. More often than not, success proves fleeting. Argentina, Greece, and Venezuela all reached Western income levels in the last century but then fell back. Today, in addition to Mexico and the Philippines, Peru and Thailand are making their run. These four nations share a trait common to many star economies of recent decades: a charismatic political leader who understands economic reform and has the popular mandate to get it enacted. Still, excitement should be tempered. Such reformist streaks tend to last three to five years. So don’t expect the dawn of a Filipino or a Mexican century. BALANCING ACT If forecasters need to think small in terms of time, they need to think big when it comes to complexity. To sustain rapid growth, leaders must balance a wide range of factors, and the list changes as a country grows richer. Simple projects, such as paving roads, can do more to boost a poor economy than a premature push to develop cutting-edge technologies, but soon the benefits of basic infrastructure run their course. The list of factors to watch also changes with economic conditions. Five years after the global financial crisis, too much credit is still a critical problem, particularly if it grows faster than GDP. Indeed, too much credit is weighing down emerging economies, such as China, which have been running up debt to maintain economic growth. Once touted as the next China, Vietnam has in fact beaten China to the endgame, but not the one it expected: Vietnam has already suffered a debt-induced economic meltdown and is only now beginning to pick up the pieces and shutter its insolvent banks. To keep their economies humming, leaders need to make sure growth is balanced across national accounts (not too dependent on borrowing), social classes (not concentrated in the hands of a few billionaires), geographic regions (not hoarded in the capital), and productive industries (not focused in corruption-prone industries such as oil). And they must balance all these factors at a point that is appropriate for their countries’ income levels. For example, Brazil is spending too much to build a welfare state too large for a country with an average income of $11,000. Meanwhile, South Korea, a country with twice the average income of Brazil, is spending too little on social programs. Many leaders see certain economic vices as timeless, generic problems of development, but in reality, there is a balancing point even for avarice and venality. Inequality tends to rise in the early stages of economic growth and then plateau before it begins to fall, typically at around the $5,000 per capita income level. On this curve, inequality relative to income level is much higher than the norm in Brazil and South Africa, but it is right in line with the norm -- and therefore much less worrisome -- in Poland and South Korea. The same income-adjusted approach also applies to corruption and shows, for example, that Chile is surprisingly clean for its income level, while Russia is disproportionately corrupt. ASK A LOCAL No amount of theory, however, can trump local knowledge. Locals often know which way the economy is turning before it shows up in forecasting numbers. Even before India’s economy started slowing down, Indian businesspeople foretold its slump in a chorus of complaints about corruption at home. The rising cost of bribing government officials was compelling them to invest abroad, although foreign investors still poured in. There is no substitute for getting out and seeing what is happening on the ground. Analysts who focus on dangerously high levels of investment in emerging nations use China as a test case, since investment there is nearly 50 percent of GDP, a level unprecedented in any developed country. But the risk becomes apparent only when one goes to China and sees where all the money is going: into high-rise ghost towns and other empty developments. On the flip side are Brazil and Russia, where anemic investment levels account for grossly underperforming service sectors, inadequate roads, and, in São Paulo, the sight of CEOs who dodge permanently clogged streets by depending on a network of rooftop helipads. Economists tend to ignore the story of people and politics as too soft to quantify and incorporate into forecasting models. Instead, they study policy through hard numbers, such as government spending or interest rates. But numbers cannot capture the energy that a vibrant leader such as Mexico’s new president, Enrique Peña Nieto, or the Philippines’ Benigno Aquino III can unleash by cracking down on monopolists, bribers, and dysfunctional bureaucrats. Any pragmatic approach to spotting the likely winners of the next emerging-market boom should reflect this reality and the fundamentally impermanent state of global competition. A would-be forecaster must track a shifting list of a dozen factors, from politics to credit and investment flows, to assess the growth prospects of each emerging nation over the next three to five years -- the only useful time frame for political leaders, businesspeople, investors, or anyone else with a stake in current events. This approach offers no provocative forecasts for 2100, no prophecies based on the long sweep of history. It aims to produce a practical guide for following the rise and fall of nations in real time and in the foreseeable future: this decade, not the next or those beyond it. It may not be dramatic. But the recent crash highlighted just how dangerous too much drama can be. |

Showing posts with label developing market. Show all posts

Showing posts with label developing market. Show all posts

Sunday, December 22, 2013

Why Economic Forecasts Fail

Labels:

developing market,

economics,

economist,

growth

Thursday, May 5, 2011

Is your emerging-market strategy local enough?

The diversity and dynamism of China, India, and Brazil defy any one-size-fits-all approach. But by targeting city clusters within them, companies can seize growth opportunities.

Creating a powerful emerging-market strategy has moved to the top of the growth agendas of many multinational companies, and for good reason: in 15 years’ time, 57 percent of the nearly one billion households with earnings greater than $20,0001 a year will live in the developing world. Seven emerging economies—China, India, Brazil, Mexico, Russia, Turkey, and Indonesia—are expected to contribute about 45 percent of global GDP growth in the coming decade. Emerging markets will represent an even larger share of the growth in product categories, such as automobiles, that are highly mature in developed economies.Figures like these create a real sense of urgency among many multinationals, which recognize that they aren’t currently tapping into those growth opportunities with sufficient speed or scale. Even China, forecast to create over half of all GDP growth in those seven developing economies, remains a relatively small market for most multinational corporations—5 to 10 percent of global sales; often less in profits.

To accelerate growth in China, India, Brazil, and other large emerging markets, it isn’t enough, as many multinationals do, to develop a country-level strategy. Opportunities in these markets are also rapidly moving beyond the largest cities, often the focus of many of these companies. For sure, the top cities are important: by 2030, Mumbai’s economy, for example, is expected to be larger than Malaysia’s is today. Even so, Mumbai would in that year represent only 5 percent of India’s economy and the country’s 14 largest cities, 24 percent. China has roughly 150 cities with at least one million inhabitants. Their population and income characteristics are so different and changing so rapidly that our forecasts for their consumption of a given product category, over the next five to ten years, can range from a drop in sales to growth five times the national average.

Understanding such variability can help companies invest more shrewdly and ahead of the competition rather than following others into the fiercest battlefields. Consider Brazil’s São Paulo state, where the economy is larger than all of Argentina’s, competitive intensity is high, and retail prices are lower than elsewhere in the country. By contrast, in Brazil’s northeast—the populous but historically poorest part of the country—the economy is growing much faster, competition is lighter, and prices are higher. Multinationals short on granular insights and capabilities tended to flock to São Paulo and to miss the opportunities in the northeast. It’s only recently that they’ve started investing heavily there—trying to catch up with regional companies in what is often described as Brazil’s “new growth frontier.”

As developing economies become increasingly diverse and competitive, multinationals will need strategic approaches to understand such variance within countries and to concentrate resources on the most promising submarkets—perhaps 20, 30, or 40 different ones within a country. Of course, most leading corporations have learned to address different markets in Europe and the United States. But in the emerging world, there is a compelling case for learning the ropes much faster than most companies feel comfortable doing.

The appropriate strategic approach will depend on the characteristics of a national market (including its stage of urbanization), as well as a company’s size, position, and aspirations in it. In this article, we explore in detail a “city cluster” approach, which targets groups of relatively homogenous, fast-growing cities in China. In India, where widespread urbanization is still gaining steam, we briefly look at similar ways of gaining substantial market coverage in a cost-effective way. Finally, in Brazil we quickly describe how growth is becoming more geographically dispersed and what that means for growth strategies.

Targeting the right city clusters in China

By segmenting Chinese cities according to such factors as industry structure, demographics, scale, geographic proximity, and consumer characteristics, we identified 22 city clusters, each homogenous enough to be considered one market for strategic decision making (Exhibit 1). Prioritizing several clusters or sequencing the order in which they are targeted can help a company boost the effectiveness of its distribution networks, supply chains, sales forces, and media and marketing strategies.For additional detail from the authors about this exhibit, see “A Better Approach to China’s Markets,” from the March 2010 issue of the Harvard Business Review.

More specifically, this approach can help companies to address opportunities in attractive smaller cities cost effectively and to spot opportunities for, among other things, expanding within rather than across clusters (Exhibit 2)—a strategy that requires a less complex supply chain and fewer partners. Companies that nonetheless want to expand across clusters may find it easier to target 50 to 100 similar cities within four or five big clusters than cities that theoretically offer the same market opportunity but are dispersed widely across the country.

Another major benefit of concentrating resources on certain clusters is the opportunity to exploit scale and network effects that stimulate faster, more profitable growth. Because most brands still have a relatively short history in China, for example, word of mouth plays a much greater role there than it does in developed economies. By focusing on attaining substantial market share in a cluster, a brand can unleash a virtuous cycle: once it reaches a tipping point there—usually at least a 10 to 15 percent market share—its reputation is quickly boosted by word of mouth from additional users, helping it to win yet more market share without necessarily spending more on marketing.

Here are four important tips to keep in mind when designing a city cluster strategy for China.

Focus on cluster size, not city size

It’s easy to be dazzled by the size of the biggest cities, but trying to cover all of them is less effective for the simple reason that they can be very far from one another. Although Chengdu, Xi’an, and Wuhan, for example, are among the ten largest cities in China, each of them is about 1,000 kilometers away from any of the others. In Shandong province, the biggest city is Jinan, which is barely in the top 20. Yet Shandong has 21 cities among China’s 150 largest, which makes the area one of the five most attractive city clusters. Its GDP is about four times bigger than that of the cluster of cities around and including Xi’an, as well as three times bigger than the cluster of cities surrounding Chengdu.Look beyond historical growth rates

The growth of incomes and product categories is another variable that must be treated in granular fashion. Extrapolating future trends from historical patterns is particularly suspect—however detailed that history may be—because consumer spending habits change so rapidly once wealth rises.In some clusters, many people are starting to buy their first low-end domestic cars; in others, they are upgrading to imports or even to luxury brands. We expect sales of SUVs to increase at a 20 percent compound annual growth rate nationwide in the next four years, for example, but to grow as quickly as 50 percent in several cities and, potentially, even to decline in some where penetration is already deep. Similar or even sharper variance held true in almost every service or product category we analyzed, from face moisturizers to chicken burgers to flat-screen TVs. Yogurt sales in some cities are growing eight times faster than the national average.

The Shenzhen cluster has the highest share (90 percent) of middle class households—those earning over $9,000 a year. In other clusters, such as Nanchang and Changchun–Harbin, more than half of all households are still poor. As a result, people in the Shenzhen cluster are already active consumers of many categories, and the potential for growth is fairly limited. In the poorer clusters, many categories are just emerging, as larger numbers of people pass the threshold at which more goods become affordable. From a strategic viewpoint, the richer cluster could still be a major growth market for premiumgoods but not for most mass-market ones.

Don’t be fooled by generalities

Talking about Chinese consumers and how they shop is a bit like talking about European consumers. While some generalizations may be fair, certain very strong differences, even within regions, go well beyond the already significant economic variance. Guangzhou and Shenzhen, for example, are both tier-one cities, located in the same province and just two hours apart. But Guangzhou’s people mainly speak Cantonese, are mostly locally born, and like to spend time at home with family and friends. In contrast, more than 80 percent of Shenzhen’s residents are young migrants, from all across the country, who mainly speak Mandarin and spend most of their time away from their homes. To be effective, marketers will probably have to differentiate their campaigns and emphasize different channels when reaching out to the people in these two cities. That’s why we suggest managing them in different clusters, despite their proximity.The need to localize marketing activities also results from the limited reach of national media. China has over 3,000 TV channels, but just a few are available across the country. In some areas, only around 5 percent of consumers watch national television. Other media, such as newspapers and radio (and of course billboards), are even more local.

Very few companies can craft their entire strategy at the level of a cluster—those that do are usually its regional champions. But with differences such as the following common, some tailoring is critical:

- Every second consumer in Shandong believes that well-known brands are always of higher quality, and 30 percent are willing to stretch their budgets to pay a premium for the better product. In south Jiangsu, only a quarter of consumers preferred the well-known brands, and only 16 percent were willing to pay a premium for them.

- In the Shenzhen cluster, 38 percent of food and beverage shoppers found suggestions from in-store promoters to be a credible source of information, compared with only 12 percent in Nanjing.

- In Shanghai, 58 percent of residents shop for apparel in department stores, compared with only 27 percent of Beijing residents.

Allow your clusters to be flexible

Some companies may want to merge or divide clusters for strategic-management purposes. A company could, for instance, merge geographically nearby clusters, such as Guangzhou and Shenzhen or Chengdu and Chongqing, if its supply chain was well positioned to manage these proximate clusters as one. Other companies, highly driven by the media market, would find it sensible to split the Shanghai cluster into subclusters, because some markets within it are still quite different in their TV habits and other choices. By contrast, people in certain clusters, such as Chengdu or Guangzhou, watch similar TV shows across the entire cluster, so intracluster expansion allows companies to make more effective use of the media spending needed to attract consumers in the big cities.The actual number of submarkets a company opts for will depend in practice on its needs. That number should be manageable—most likely, 20 to 40. Fewer wouldn’t be likely to produce the required degree of granularity, though a company might have logistical reasons for taking this approach. More would probably be too many to run effectively.

Cost-effective market coverage in India

Often, the challenges of accessing consumption growth cost effectively are even greater in India than in China because India is less urbanized and at an earlier stage of its economic development. Companies would need to reach up to 3,500 towns and 334,000 villages, for example, to pursue opportunities in the 10 (of 28) Indian states that by 2030 will account for 73 percent of the country’s GDP and 62 percent of the urban population.To allocate financial and human resources smartly and make things more manageable, companies need to walk away from averages and adopt more granular approaches. Some companies will be well served by focusing on 12 clusters around India’s 14 largest cities. Those clusters will provide access to as much as 60 percent of the country’s urban GDP by 2030, when the 14 largest cities are likely to account for 24 percent of GDP.

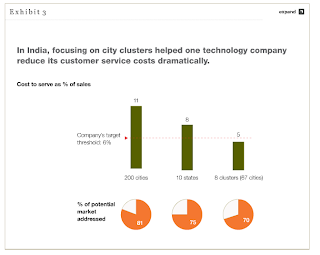

True, India’s major clusters won’t cover as much of the economy as those in China, where they will encompass 92 percent of urban GDP by 2015. Yet a hub-and-spoke approach in India should provide similar opportunities to optimize supply chains, as well as sales and marketing networks. An established technology player formerly operated in 120 cities all over India, for example. Recently, it shifted to focusing on eight clusters with a total of 67 cities, which still gave it access to 70 percent of its potential market. One benefit: customer service costs fell from a rapidly growing 9 to 10 percent of sales to a more acceptable 5 percent (Exhibit 3).

Alternatively, a company might improve the economics of its Indian business by focusing on a handful of states, an approach recently adopted by a retailer that had previously been pursuing a national footprint. Another company, this one in the consumer goods sector, recently decided to pursue opportunities in eight cities where consumers earn over $2,500 a year—more than twice the average for India—and the retail infrastructure suits its products nicely. Without this more granular analysis, the multinational would have stayed on the sidelines in the mistaken belief that Indian consumers weren’t ready for its products. It would therefore have missed the opportunity to challenge a competitor rapidly gaining the lead in those markets.

Seizing new regional opportunities in Brazil

In contrast to China and India, Brazil has been open to multinationals for decades. But during much of that time, most large companies in sectors such as consumer packaged goods focused on the southern (and most affluent) parts of the country. With just over half of the national population, this region includes São Paulo city and state, Brazil’s financial and industrial center.As economic growth accelerated in recent years, many consumers started upgrading to more sophisticated products. But growth has also been moving beyond the south and a few large cities, becoming more geographically dispersed. In the populous northeast, for example, income per capita is only half of its level in São Paulo, but the economy is growing faster than it is elsewhere in Brazil. Succeeding in new regions like the northeast requires a fresh approach for many companies. Consider the following:

- Many global companies still make the mistake of doing their consumer research in São Paulo when they are designing new products or national marketing campaigns for Brazil. They don’t realize that cosmopolitan São Paulo probably has more in common culturally with New York than with any other city in Brazil.

- Modern-format stores account for 70 percent of retailing in Brazil overall, but for only 55 percent in the northeast. To reach thousands of small (and often capital-constrained) outlets spread all over the region, packaged-goods companies must develop third-party networks specializing in frequent deliveries of goods and small drop sizes. What’s more, in Brazil as a whole, many consumer goods companies found that they had focused too much on hypermarkets when designing assortments and promotions. One company, for example, discovered that Brazil’s expanding drugstore chains were the fastest-growing channel for personal-care and beauty products. Some leading consumer goods companies have now created specialized organizations that execute distinct channel strategies in different regions and categories, with tailored product portfolios and displays.

- Many packaged-goods companies see detergent powders as a developed category in Brazil. But relatively affluent consumers there are upgrading to larger and more sophisticated washing machines, and many consumers in the northeast are buying their first fully automated machines. New detergent formulas therefore have enormous potential—annual consumption in the northeast is less than half of what it is in the south. Seizing this opportunity requires an understanding of the regional consumer, however, particularly pack size preferences (Exhibit 4). Consumers in the northeast also want a strong perfume and great quantities of foam but care less about whitening power.

There is no one-size-fits-all strategy for capturing consumer growth in emerging markets. What’s clear, though, is that traditional country strategies and other aggregated approaches will miss the mark because they can’t account for the variability and rapid change in these markets. As the battle for the wallet of the emerging-market consumer shifts into higher gear, companies that think about growth opportunities at a more granular level have a better chance of winning.

McKinsey on Finance on iPad

https://www.mckinseyquarterly.com/Is_your_emerging_market_strategy_local_enough_2790

Labels:

brazil,

china,

developing market,

india,

market segment,

mckinsey,

strategy

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)